Climate change is hard on cattle production

Who's noticed that things have gotten a little hotter out there lately? U.S. temperature trends show that the last 2 decades have been the hottest in recorded history (USGCRP, 2014).

|

| U.S. temperature change 1991-2012 Figure source: NOAA NCDC/CICS-NC |

Just like humans, cattle are feeling the heat of climate change. Heat-stressed cattle can experience fertility problems, decreases in milk production, and lower weight gains, seriously negatively impacting a rancher's bottom line. The majority of cattle being raised in the United States today are black Angus cattle, which originate from a Scottish breed much better suited to cold, snowy weather conditions than the dry or semi-tropical hot conditions found in much of the U.S. To improve cattle performance in the hotter regions of the Western and Southwestern U.S., ranchers are turning to breeds with higher levels of heat tolerance, such as the Senepol.

Senepol cattle can stand the heat

|

| Photo courtesy of The Senepol Cattle Breeders Association www.senepolbreeders.com |

Senepol cattle originated in the Virgin Islands, the result of a cross between West African N'Dama cattle, brought to the islands in the 1800's, and Red Poll cattle, an English breed introduced in the early 1900's. Before the breed made its way to the mainland United States in the 1977, these cattle developed a unique ability to maximize performance in a harsh, semi-tropical environment. Senepol cattle rival native African cattle breeds in their ability to grow and raise their calves in hot environments, but do not possess the distinctive humped back and loose folds of neck skin that often causes these breeds to be classified as 'exotic-influenced' breeds and discounted at cattle sales dominated by European breeds (SCBA, 2016).

|

| Angus-Senepol cross-bred cattle take a break from grazing during the hot Oklahoma summer Photo by Erin Campbell-Craven |

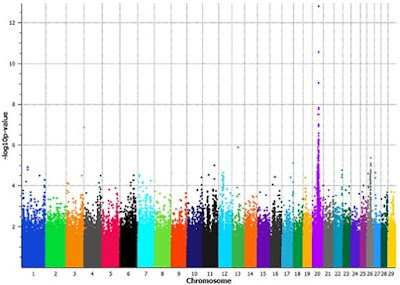

One of the main adaptations developed by the Senepol breed to maintain performance in hot climates lies in a mutation, resulting in a very short, sleek hair coat with fewer hair follicles and larger sweat glands. This mutation, referred to by researchers, is know as the SLICK hair gene. Cattle dominant for the gene can more effectively regulate their body temperature through decreased rates of sunlight absorption and increased rates of heat loss through the skin by sweating (Olson, 2003). Researchers have not been able to pinpoint where and when the SLICK hair gene arose, but have recently mapped the gene locus to the 20th chromosome found in cattle (Huson et al., 2014).

|

| Manhattan plot of slick-haired and non-slick-haired cattle breeds, demonstrating a strong association between slick-hair type cattle and chromosome 20 Figure source: Huson et al., 2014 |

Using the SLICK hair gene to help other cattle breeds keep their cool

Crossbreeding with purebred Senepol has been show to improve heat tolerance in both European dairy and beef breeds. In 2012, researchers at the University of Florida compared heat tolerance in cross-bred dairy cows composed of 75% Holstein parentage and 25% Senepol. The cows were exposed to temperatures up to 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit) in combination with 70% to 95% humidity. Researchers measured the internal temperature, respiration rate in breaths per minute, skin temperature, and sweating rate in both slick-haired and normal-haired cross-bred dairy cows to assess whether slick-haired cows would function better under these extreme conditions. As shown by the graphs below, the slick-haired cows (closed triangles) had lower internal and external temperatures than the normal-haired cows (open and closed circles), as well as lower respiration rates and higher sweating rates. All of these factors combined to increase heat tolerance in the slick-haired cows (Dikmen et al., 2014).

|

| Responses to heat stress in slick-haired and normal-haired cross-bred dairy cows Figure source: Dikmen et al., 2014 |

As seen below, the researchers also measured milk production in the cross-bred cows during 90 days periods in the summer (open circles) and winter (closed circles), and noticed that cows with the SLICK hair gene produced more consistent amounts of milk year-round that cows with normal hair. Cows with normal hair produced lower amounts of milk during the summer due to heat stress, meaning that introducing more cross-bred cows with the SLICK hair gene into dairy herds could help farmers keep milk production more stable year-round (Dikmen et al., 2014).

|

| Milk yield in slick-haired and normal-haired cross-bred dairy cows during 90-day periods in the winter and summer Figure source: Dikmen et al., 2014 |

In another study, which took place in southern Texas, slick-haired beef calves were also found to wean at higher weights than normal-haired or hairy calves. These calves were born to composite breed beef cows that were a mix of Senepol, Red Angus, and Tuli (another African-derived breed), and were all either red or light-colored, helping them stay cooler than black cows in similar climates (Lukefahr, 2017).

|

| Slick-haired, light-colored composite breed composed of Red Senepol, Red Angus, and Tuli Photo source: Lukefahr, 2017 |

As shown in the figure below, slick-haired red calves born to red and light-colored cows, as well as light calves born to red cows, all reached higher weights by the time they were weaned than their hairy counterparts. The only calves that showed no difference in weight gain due to hair type were the light-colored calves born to light cows, which may be due to the fact that these cow-calf pairs are already so heat-tolerant that hair type makes little difference. It has been hypothesized that these higher calf weights are due to more heat-tolerant cow-calf pairs spending more time grazing during the hot summer months than less heat-tolerant cattle. In order to support this idea, researchers will need to observe these slick-haired pairs more closely in order to measure their time spent grazing and see how it compares to the average time spent grazing by cows and calves with hairier coats (Lukefahr, 2017).

|

| Weaning weights for hairy and slick-haired calves, paired by cow-calf color Figure source: Lukefahr, 2017 |

Cattle of the future?

Clearly, there is a lot more to learn about how to best keep breeding high-performing cattle to fit our changing climate, with most of the research on the topic being done very recently (within the last 15 years). Although ranchers have been cross-breeding cattle for centuries in order to best fit their livestock to their environments, never before have they needed to adapt so rapidly to an increasingly warm climate. Hopefully researchers at colleges and universities will continue to step up do the hard work that needs to be done in order to help ranchers keep our cattle cool.

|

| Photo by Erin Campbell-Craven |

REFERENCES

Dikmen, S., Khan, F.A., Huson, H.J., Sonstegard, T.S., Moss, J.I., Dahl, G.E., and P.J. Hansen. 2014. The SLICK hair locus derived from Senepol cattle confers thermotolerance to intensively managed lactating Holstein cows. Journal of Dairy Science 97(9):5508-5520.

Huson, H.J., Kim, E., Godfrey, R.W., Olson, T.A., McClure, M.C., Chase, C.C., Rizzi, R., O’Brien, A.M.P., Van Tassell, C.P., Garcia, J.F., and T.S. Sonstegard. Genome-wide association study and ancestral origins of the slick-hair coat in tropically adapted cattle. Frontiers in Genetics 5(101):1-12.

Lukefahr, S.D. 2017. Characterization of a composite population of beef cattle in subtropical south Texas and the effect of genes for coat type and color on preweaning growth and influence of summer breeding on sex ratio. The Professional Animal Scientist 33:604-615.

Mariasegaram, M., Chase, C.C, Chaparro, J.X., Olson, T.A., Brenneman, R.A., and R.P. Niedz. The slick hair coat locus maps to chromosome 20 in Senepol-derived cattle. Animal Genetics 38:54-59.

Olson, T.A., Lucena, C., Chase, C.C., and A.C. Hammond. 2003. Evidence of a major gene influencing hair length and heat tolerance in Bos taurus cattle. Journal of Animal Science 81:80-90.

Mariasegaram, M., Chase, C.C, Chaparro, J.X., Olson, T.A., Brenneman, R.A., and R.P. Niedz. The slick hair coat locus maps to chromosome 20 in Senepol-derived cattle. Animal Genetics 38:54-59.

Olson, T.A., Lucena, C., Chase, C.C., and A.C. Hammond. 2003. Evidence of a major gene influencing hair length and heat tolerance in Bos taurus cattle. Journal of Animal Science 81:80-90.

Senepol Cattle Breeders Association (SCBA). 2016.

www.senepolcattle.com

U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP). 2014. Climate change impacts in the United States: U.S. national climate assessment.

U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP). 2014. Climate change impacts in the United States: U.S. national climate assessment.

Who knew? I think so many of us take for granted that cows are part of the landscape and meat/dairy are part of our diets without giving much thought as to the process or though behind either of those truths. I especially hadn't considered the impact climate change could have on the cattle industry. Glad that scientists and ranchers are working on this very important issue. Very interesting and relevant blog post!

ReplyDeleteDo Pineywood cattle have the slick gene?

ReplyDelete